Last time, I wrote about what it was like to be a conference volunteer. This time, I’ll be writing about my experience as an attendee.

I. The Technical

My final marks in Physics 1 and Physics 2 were 99 and 100, respectively, so it’s probably safe to say that, relative to other first years, my physics knowledge is definitely not awful. But attending a bunch of talks given by people who have been researching in their fields for years or even decades made me feel like I knew about as much as this guy:

For example, the first day of the conference consisted of three tutorial sessions, intended to introduce those who are unfamiliar to the areas of field electron emission, optical electron emission, and thermal electron emission. However, “unfamiliar” seems to be a bit of a relative term, since this was more or less my stream-of-consciousness thoughts during the first session I attended:

Fowler-Nordheim? Schottky? Is this just a thing in physics that we refer to equations by last name? How am I supposed to know what they describe if I can’t see them? Gah, okay, TUNNELLING, yes, I’ve heard of that – it wasn’t part of the first year physics curricula, but I know of it. And FLYOVER – okay so that’s basically the opposite of tunnelling. Yay! I think I’m starting to get this. Okay, now there’s a chart with 5 lines on it… oh god what do those lines mean….

Needless to say, I very quickly gave up on the idea that I would be able to understand anything with any level of detail at all and started treating it instead as a chance to see, broadly, what types of questions people are most interested in asking in the field of solid state physics research. If I were going to start grad school in the next year or two, I probably would have been able to find quite a few ideas for a grad school application research proposal.

There were also a few little “aha!” moments, which I want to record for posterity, because one day I will probably look back and think it’s hilarious that I had to have an “aha!” moment at all about these things:

- Plane waves: at one point, a speaker talked about plane waves as something that does not actually exist and therefore are inadequate to use in modelling, which, of course, got me wondering, “What are plane waves?” Fortunately, the speaker went on to drop hints such as “continues propagating forever” and “phase position is a perfect function of time,” until I finally realised, plane waves are what first years learn as “waves.” “Waves,” as I have learned it, don’t exist. Aw, shucks….

- One speaker, presenting on thermal electron emission, spoke of using acoustic fields to stimulate electron emission. “Huh, I didn’t know sound could cause electron emission,” I said to myself, and then I realised that his talk was on thermal electron emission, and then I remembered that sound is just particles knocking into each other and that heat is… also particles knocking into each other. Sound = heat. Mind blown.

II. The Social

Spoiler alert: this never happened

Spoiler alert: this never happened

Initially, I was apprehensive about rubbing shoulders with established scientists as well as grad students at the best schools in the world (schools like MIT, Stanford, etc. were well represented among the attendees). But everyone I met was incredibly welcoming and more than happy to dumb down their research for an interested newbie.

I found myself using this line a lot:

Can you explain your research in terms that an undergrad entering second year will understand?

And it pretty much always worked. I mean, at least, all of them were happy to try. Sometimes they didn’t entirely succeed, but nobody told me to go away or anything, and I almost always did get something new out of it, even if the “something new” was as simple as “There is a company in Washington making 5-million-dollar microscopes that are approaching 0.5 angstrom resolution, and the science behind resolving images at that scale is… really really complicated.”

When a speaker managed to make a presentation that I could understand, which did happen occasionally, if I ran into them afterward, I thanked them for making their presentation accessible to an undergraduate. For the most part, they were super happy to get positive feedback. (Apparently, this is actually something the director of the Max Planck Institute really worries about when writing his speeches. Who knew?)

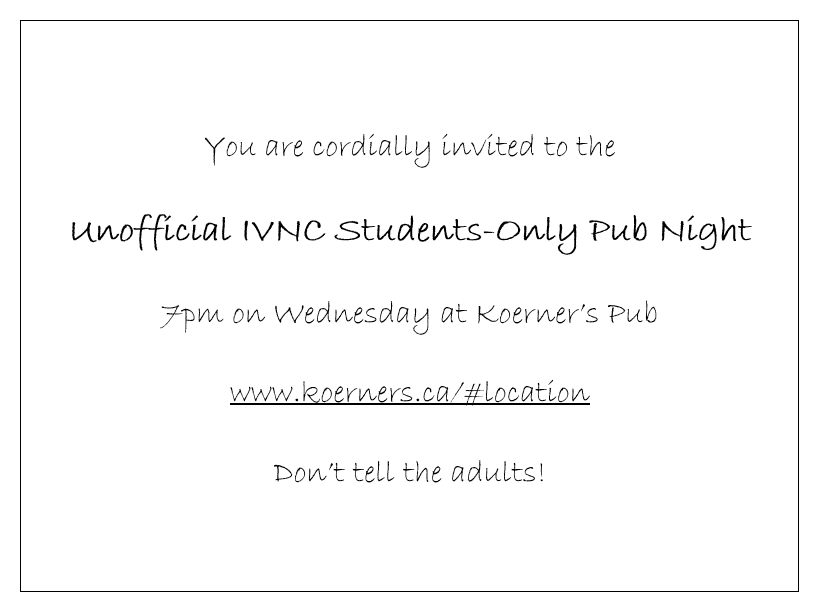

My fellow volunteers also had the brilliant idea to organize a students-only pub night, for which I created this super fancy invitation:

Which we passed out, very secret-like, to everybody who looked like they were roughly in the correct age range to be a student.

This event turned out to be a blast. I got to meet students from all over the world, plus a few industry representatives who got an invite on the basis that they looked like they could be students. Several of the invitees also expressed how much they liked the event and thought more conferences should have events that force students from different schools to mingle independently of their supervisors. This sentiment surprised me, as I had assumed it would be a pretty common type of event. Not so, apparently.

The take-away here is, if you’re ever a student volunteering at or even just attending a conference, organize a pub night for the other students. You will have fun and feel very popular and also hear many awful physics jokes.

III.

I witnessed a feeding frenzy. It was scary, but fascinating.

After each presentation, there was a 5-10 minute question period. For most presentations, the questions were polite requests for clarification: a lot of “Why did you use Material X?” or “Is Condition Y really necessary to induce emission?” Even some of the more junior presenters whose work did not seem particularly ground-breaking were mostly met with friendly and encouraging curiosity.

But one of the presenters was… well, the word that jumps to mind is “eviscerated.” There was a full 15 minutes of variations on “How can you claim that your device will work when you used such rudimentary modelling for X?”, where X was every component the proposed device had. I felt very sorry for the presenter, though I did understand some of the objections.

The take-away: never, ever, under any circumstances, claim that something will work unless you’ve actually built and thoroughly tested it. Even then, maybe just say that your prototype seems to work and further research is needed.

IV.

The most awful (awesome?) physics joke went as follows:

We toured the UBC Botanical Garden, which is bisected by Marine Drive. A tunnel runs under the (raised) road to connect the two halves of the Garden. When the tour guide lead us to the tunnel, one person commented that the barrier between the two sides was far too high – so, it was fortunate that we could tunnel through it.

Two IVNC visitors, tunnelling across Marine Drive

Two IVNC visitors, tunnelling across Marine Drive